Mavencook was a new startup that I worked with to tackle a question: How might we improve the recipe for the modern era?

5 min skim ⋅ 15 min read

Problem

The process of learning cooking has not changed in a long time. With the advent of widespread mobile internet, we now have a lot of content at our fingertips - but the general process remains the same: you can try to follow a recipe, or attend a cooking class in person. The former is unreliable and difficult, and the latter is expensive and time consuming.

Role

I was responsible for all aspects of the product. Systems and Product design, UX research, UI, Prototyping, Testing, Branding and Identity.

Deliverables

With the team, I brought the product from discovery/idea phase to alpha launch.

Process

My design process was nonlinear and involved many different stages. This is a summary of the highlights in their general order of execution.

1

Discovery and Needfinding

Conducted exploratory research and ideation to set the direction of the project.

2

Design for Education

Researched pain points, practices, and innovations in education and applied them to the problem.

3

Design for Navigation

Identified and researched road navigation as an analagous situation to guide our communication design.

4

5

Flow and Prototyping

Designed the flow and created prototypes through a number of iterations.

6

Design for Failure

Identified and researched failure scenarios and designed protocols to contain them.

7

1

Discovery and Needfinding

Abstract

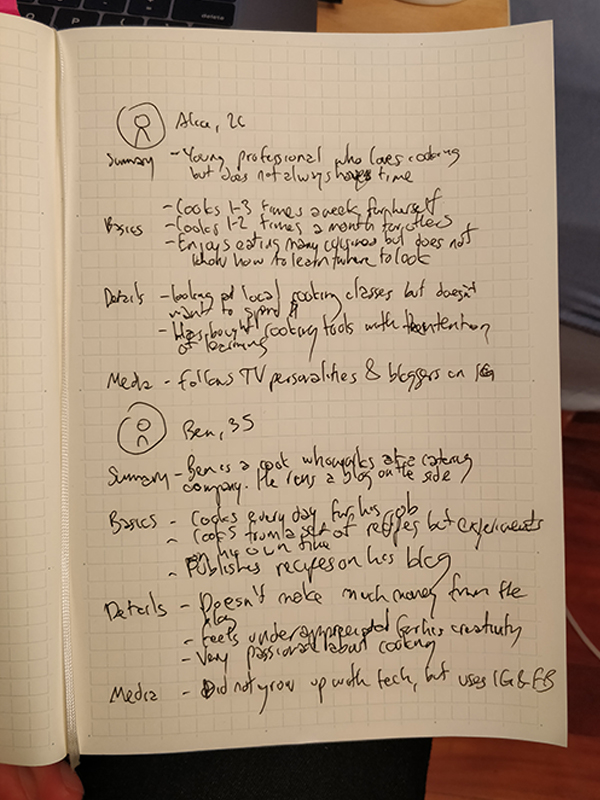

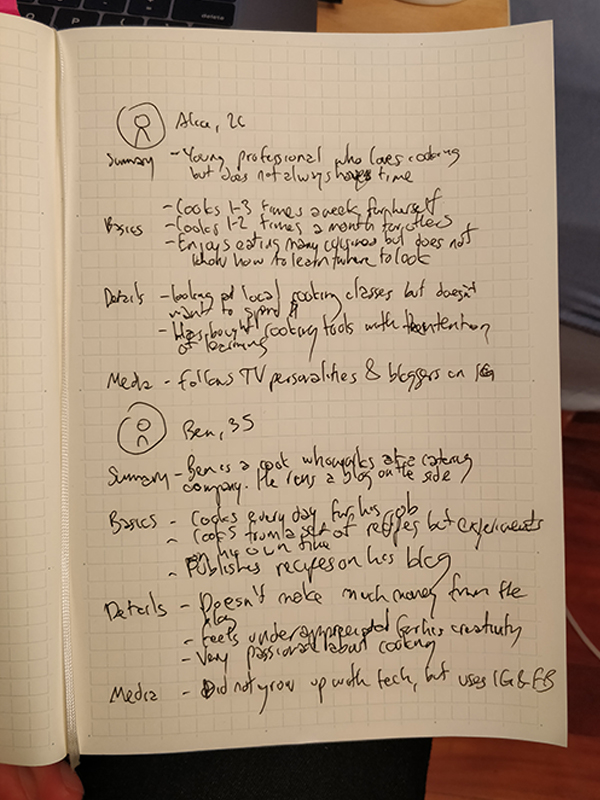

We wanted to understand the pain points in the process. Identified people of different levels of cooking experience segmented into two categories: professional and home. Observed them cook, and conducted ethnographies afterwards. Identified four main pain points in the cooking process.

In order to build a product for cooking, we needed to first understand the pain points in the process of learning to cook a new dish. In initial discovery, I talked to people with a wide variety of cooking experience.

"How might we improve the cooking experience with a mobile platform?"

Research goal:

Identify pain points in the cooking process

Research method:

Observed people cook, half of whom were professional cooks and half of whom were home cooks. Conducted a series of ethnographies to identify pain points in the cooking process.

Research results:

From ethnographies, we identified a series of insights that shed light on the main pain points in the process of learning to cook.

- We tend to stick to our comfort zone - what we already know. Decisions are hard, and time is valuable. This was true for both user groups, on different scales.

- Information quality is unreliable. There are so many recipes for any given dish out there, and no way to tell if they’re good or not short of experience. Many professional chefs will study 10-15 different recipes and assimilate the information before attempting a new dish. Home chefs often choose one semi-arbitrarily and hope for the best.

- Failure is discouraging. Especially for home cooks, for whom cooking is the primary mode of sustenance, making a mistake means dealing with the consequences - throwing it away or sucking it up and eating it. Trial and error is a great way of learning, except when trial is time consuming and errors can be catastrophic.

- Preparation is important. In a professional kitchen, cooks will often hold a briefing prior to a session. Understanding the timing, ingredients, dynamics, and intricacies of each dish prior to execution is key to timely, successful cooking, and can cut cooking time significantly. This includes meta-knowledge that is often difficult to communicate in writing, because it is both broad and situationally specific.

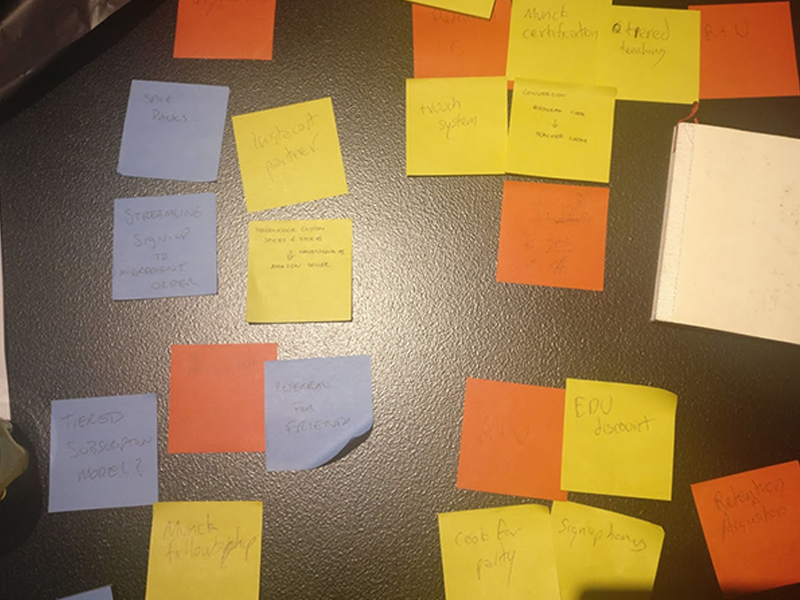

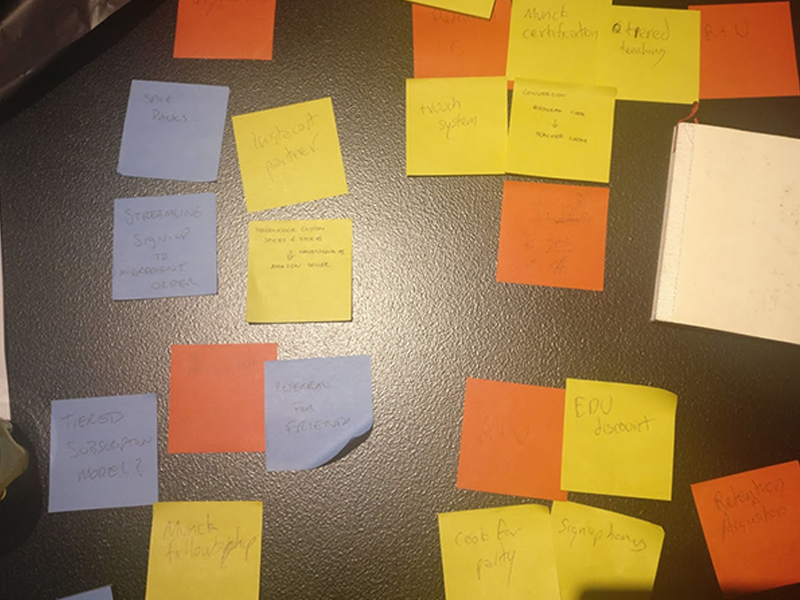

From data gathered in interviews, we conducted brainstorming sessions exploring the problem and solution space, identified candidates for users that we wanted to keep in touch with throughout design and development, developed profiles, and mapped learnings. With these insights to frame the process, I continued with deeper research.

Reflections

The assumption was that people with varying levels of experience approach cooking differently. Due to the broad problem we were tackling, I didn't delineate higher resolution categories at this stage - perhaps we would have learned more, but at the time we wanted to explore broadly before narrowing down to prevent overfitting over arbitrary categories.

2

Design for Education

Abstract

Researched education as a vertical with analogous problems and solutions. Set up a series of experiments to validate assumptions in which an instructor led a student through the cooking process over an existing videochat platform. Received positive feedback, and discovered three core insights into the process and dynamics of cooking instruction. Used this data to iterate our problem statement.

Cooking is a learning process, so I studied the cooking process through the lens of our education system.

Traditionally, the American education system has been curriculum-based, with teachers as a standardized mode of delivery. We know there is no one-size-fits-all approach to learning, and yet we continue to instruct and evaluate students on a standardized, uniform basis. Other countries, like Finland, have seen huge success in adopting a human-centered educational model, with quality teachers at the center in a curriculum that adapts to the individual needs and dynamics of each student and teacher. This process has paid off, with Finland consistently ranking significantly above the US across the board in many educational metrics.

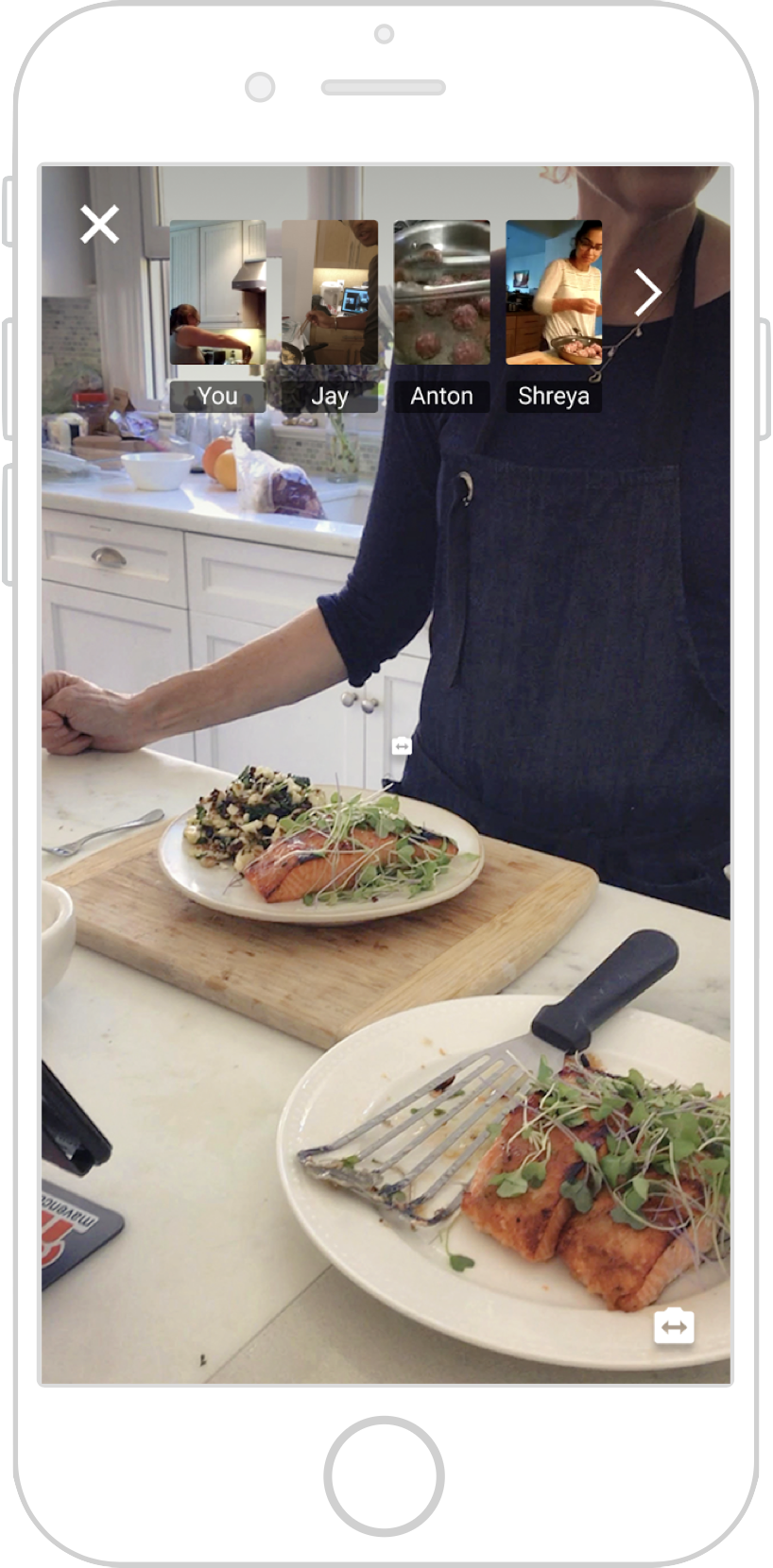

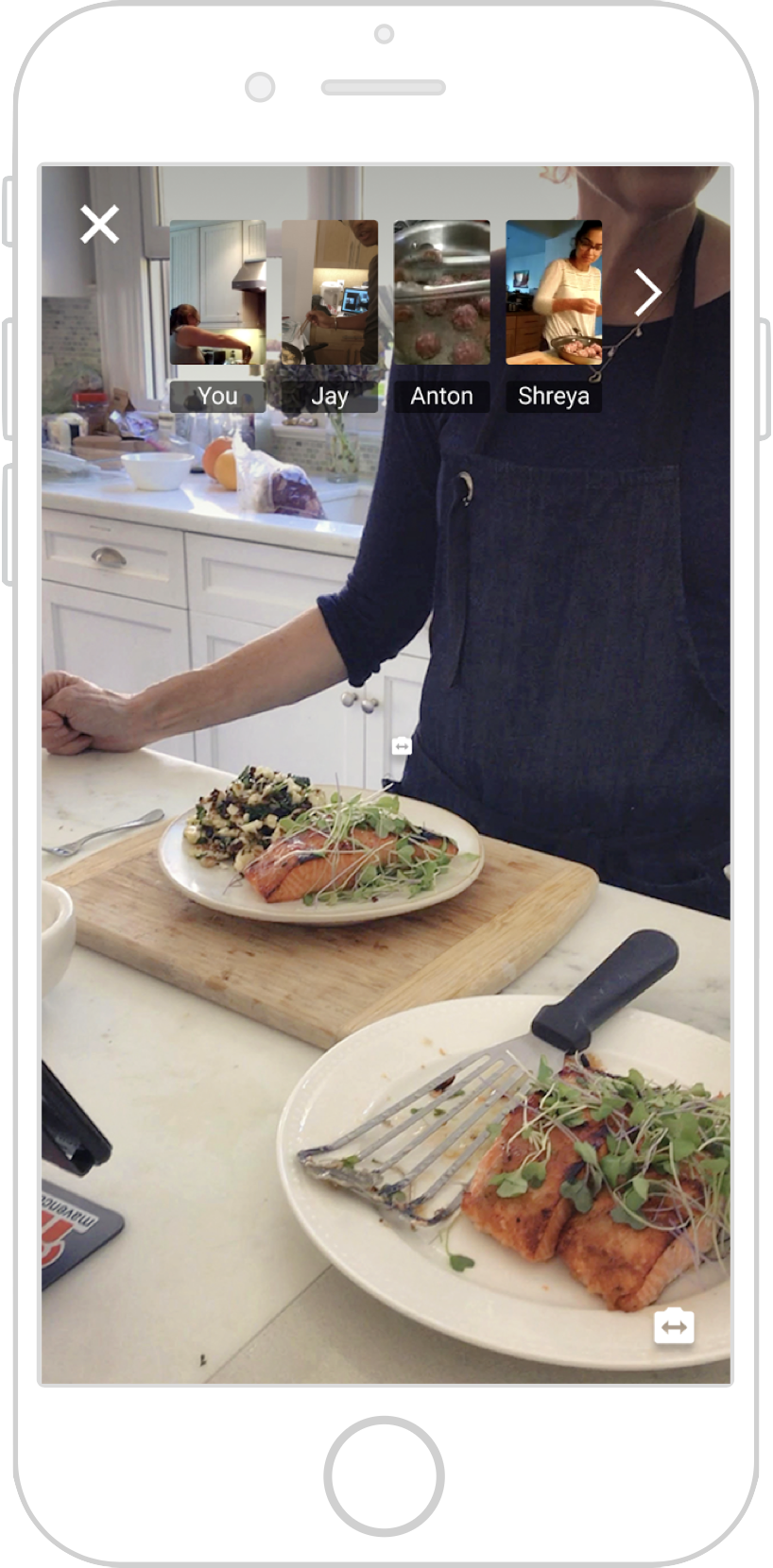

I made the assumption that cooking, like education, faced a similar scenario: that learning cooking is more about people than the recipe. We wanted to validate that the dynamic of human interaction through a videochat channel provided a more rewarding cooking experience than one-way learning through recipes (cookbooks and videos, etc).

Research goal:

Validate our assumptions and gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics of live cooking in an educational context by testing this hypothesis.

Research method:

We set up cooking sessions with five participants, with the requirement that each user had to have learned at least one new dish from an online recipe within the last month. These participants were then taught a recipe through video chat by a chef. I observed the sessions and interviewed the subjects.

Research results:

Reactions were overwhelmingly positive, and we identified a series of insights into the dynamics of the scenario.

- Cooking alone for yourself is lonely. Having other people there virtually makes it much more fun, because it feels like you're cooking with/for a big family. Kerry “I love cooking with my daughter and her boyfriend. This was really fun, and it kind of felt similar"

- Recipes are just guidelines - and being able to get advice in real time is a missing piece of the puzzle that makes the experience more complete and more rewarding. Jay “It was really helpful being able to see what she was doing and getting feedback"

- Live feedback is about more than just fixing mistakes. In multiple instances, significant mistakes were caught by the chef and fixed before further damage could have been done. However, participants mentioned that even when things were going well, they felt a lot more confident executing with a responsive host.

Our participants talked as much about the chef as they did about the food. Most of them reached out to us afterwards to ask about doing future sessions, and stressed that making a dish perfectly on the first try was incredibly rewarding.

We interpreted this as a strong indicator that

- - Cooking is a learning process and faces similar problems as education in general

- - We cannot ignore the role of people in any form of education, and human-centered instruction is successful for teaching cooking

- - Live video chat is a promising channel for cooking together

With these results, I refined our problem statement:

"How might we create a platform for cooking education centered around live videochat?"

Next, I focused on the problem from another angle.

Reflections

It felt good to have strong validation that we were on the right track. However, in hindsight I think it would have been userful to delve deeper into the individual host-student dynamic at this step - it would have saved time when designing for failure (section 6), and would have been useful in fleshing out user profiles more deeply.

3

Design for Navigation

Abstract

Abstracted the dynamics of the problem in search of analogous situations. Identified and researched road navigation. Surveyed information and communications design in popular navigation apps and used this frame to understand analogous problems in cooking. Summarized insights and aligned mental models to design and refine our framework for cooking.

From here, I started working on user stories, assessing features, and mapping out the flow, but I also continued exploration the problem from another perspective.

I extracted the dynamics of the problem from its context in search of analogous situations. We searched a case in which:

- The previously identified pain points were relevant and significant

- The experience was similar - users read and execute a set of instructions in a changing real-time situation in pursuit of a final goal

- The platform was on mobile

We considered a number of possible cases and arrived at the analogy of navigation. In road navigation, our main pain points are relevant:

- We tend to prefer the routes and roads that we know

- There are many ways to arrive at a destination, and it’s difficult to know which to pick from looking at a traditional map

- Failure is highly discouraging, whether it means being late or having an accident

- Preparation is important. It’s very helpful for the driver to study the route before executing.

I set a problem statement for this section:

"How might we communicate information for effective navigation of a recipe?"

I surveyed the most popular navigation applications. I observed people using the app (friends, uber drivers, and others), and mapped their actions and emotions during the navigation of a route, and recorded their experiences with driving. To identify relevant segments of the experience, I compared this to data and maps gathered from cooking trials. I quickly zeroed in on the pre-trip information display, which was reminiscent of the pre-cooking briefing that many kitchens practice. This phase of a trip gives the user a lot of information about the upcoming drive, which is crucial to both new drivers and experienced drivers alike - it informs a mental model of the journey ahead.

In Maps, the user is presented with the map first and is shown a large body of crucial information in a simple, clear, and concise display that communicates:

- Destination overview

- Possible routes (with steps to take) and time needed (situational details)

- Traffic, construction, accidents, (situational modifiers)

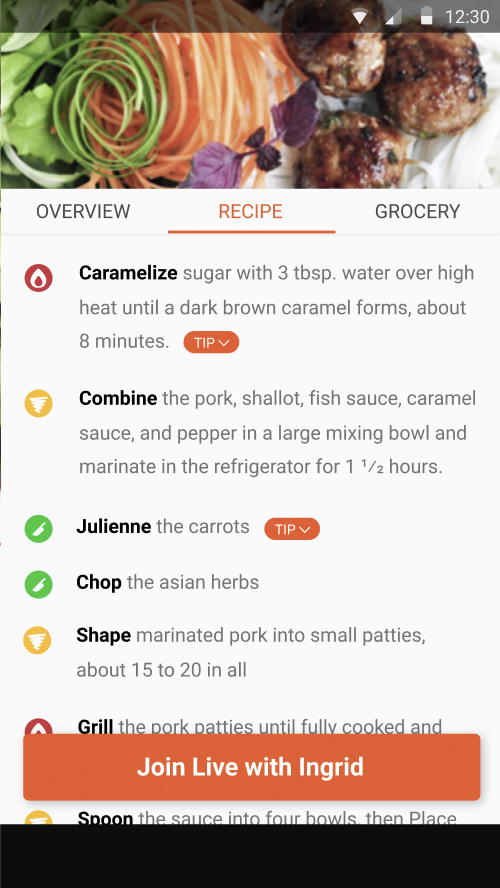

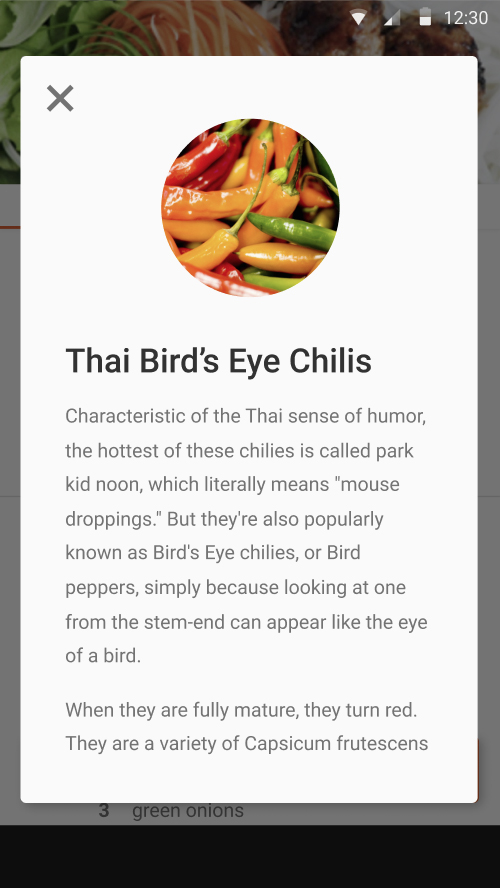

Because cooking benefits heavily from prior experience (from accumulated meta-knowledge), we wanted to communicate prior information in a streamlined, easily digestible manner that highlighted tips, pitfalls and pain points. We brainstormed to identify knowledge valuable in understanding, and refined the results into two categories of meta-knowledge (aside from the recipe) that were important for cooking well:

- Ingredient dynamics - how ingredients behave, background info, other uses, taste, culture/history, and theory.

- Chef’s tips - information related to steps, shortcuts, hacks, indicators, and parallel uses.

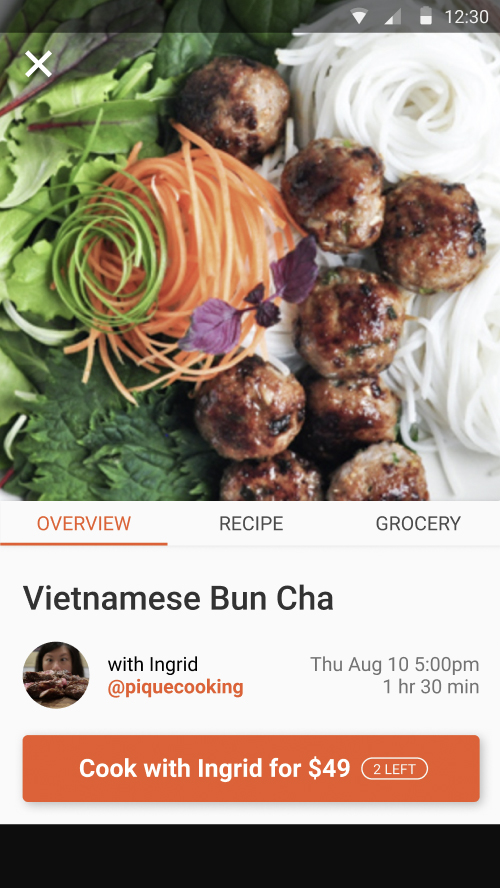

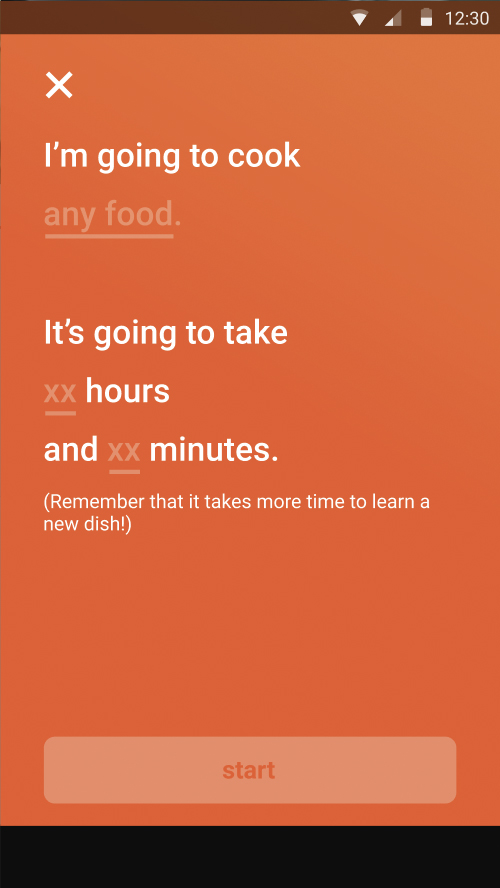

Interpreting a list of cooking steps as a route with a series of instructions, we concluded that we desired on a pre-cooking interface that clearly and concisely communicated analogous expectations:

- Recipe and host overview

- Steps to execute with personal tips (situational details)

- Materials needed with expanded info on selected ingredients (situational modifiers)

With this more robust mental model of a recipe and the information framework built on it, I moved into the design phase.

Reflections

This was one of the coolest parts of the project. There are so many parallels that it was initially difficult to decide which ones were relevant. Mapping user emotions really helped, and was very enlightening. We ended up going with the simplest complete display of information that we had at the time, but it would have been cool to run some cross-vertical tests teaching expert drivers (Uber drivers, etc.) to cook using our interface, and analyzing how expert chefs interpret navigation interfaces. During this time, I was exploring visual abstractions of recipes as well, pulling themes from another navigation vertical - public transportation maps - to do so. I ended up in some interesting places with a couple leads, but didn't end up fully exploring that world and would very much like to pursue it again. Recipes really are so inefficient at communication...

4

Making Models

Abstract

A collection of mental models showing the theory and framework that we developed around the cooking process. Each model below is just the latest iteration of a model related to a specific regime of the problem we were tackling.

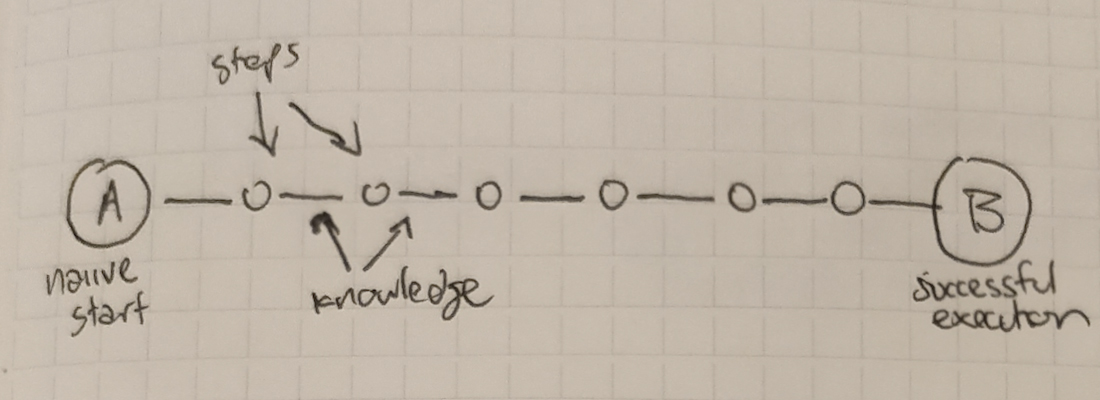

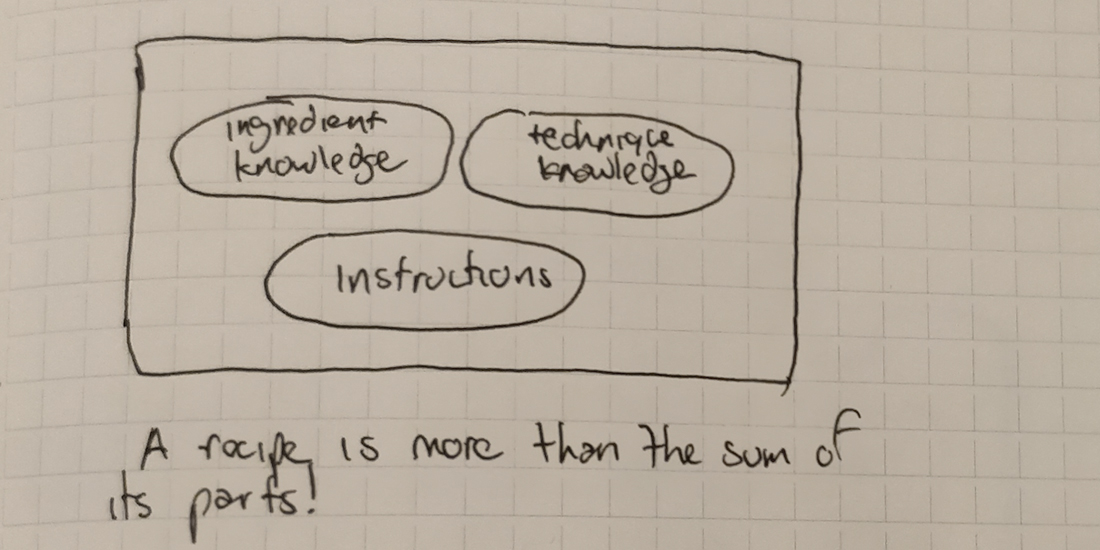

Throughout the process of designing and understanding the entire system, I continuously sketched, revised, and updated mental models to aid in framing the process. Below are some sketches and descriptions of the models that I settled on, each detailing a piece of the experience, platform, or system.

I interpreted a recipe as a route from a starting point to an ending point. Since we are a cooking education platform, I assume a naiive start (A) and a successful end (B). The points are spanned by a number of 'steps' - the actions that we see in books or online instruction sites. Steps are connected by knowledge, i.e. knowledge of execution, theory, or background related to the specific steps at hand. This is the knowledge that needs to be communicated from host to student in a class.

Another way to abstract a recipe is as the union of three elements. The base is the traditional recipe, consisting of instructions. Augmenting the instructions is knowledge of the ingredient dynamics and techniques that can be applied in the context of the instructions. The union of these three elements forms our understanding of a recipe.

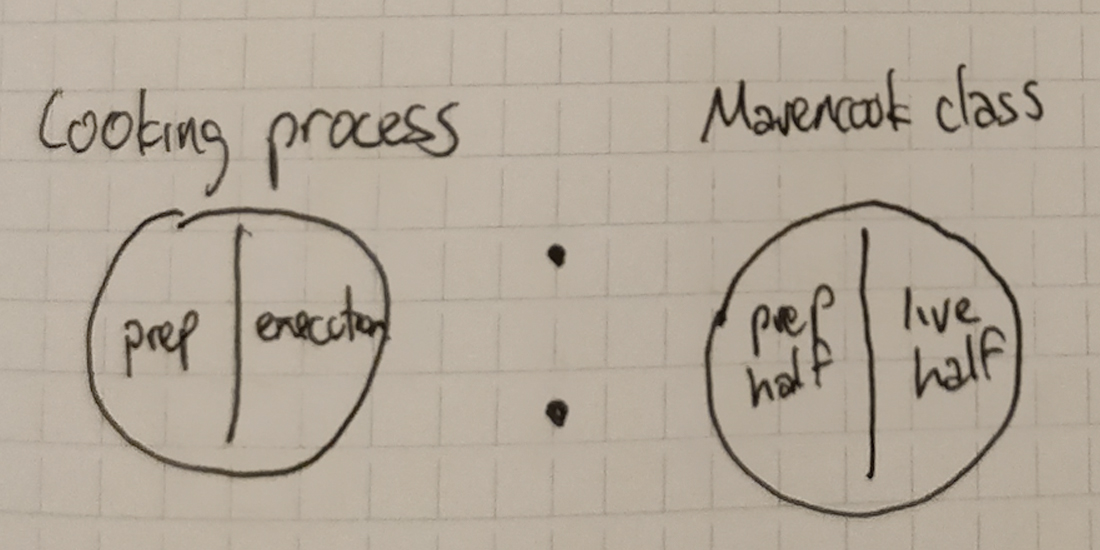

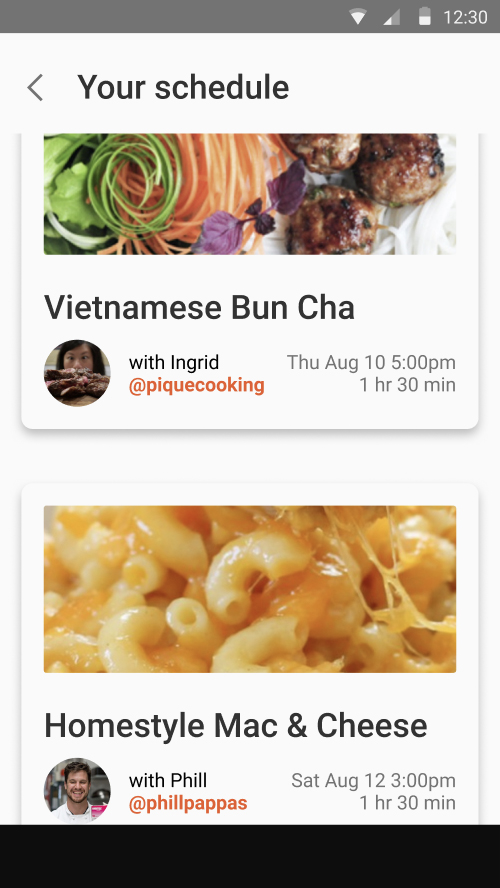

I defined our classes in the same way we understand the cooking process. In cooking, we have a prep section and an execution section. In a Mavencook class, we have a prep half consisting of a UI containing recipe information, and a live half consisting of instruction over a videochat channel. The structure and goals are analogous, the but the methods are different.

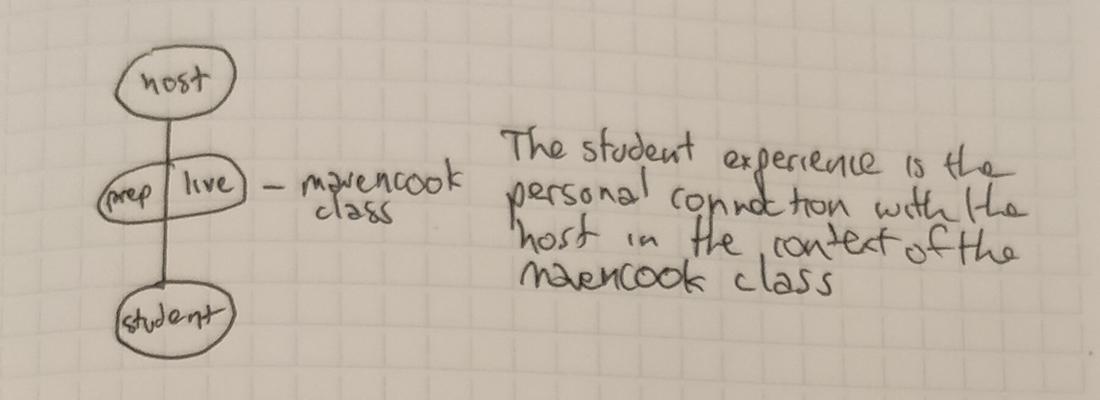

The student experience in defined by the personal connection with the host in the context of the Mavencook class - we understand food to be about people more than process. In essence, the class is the medium through which the personal connection is facilitated. The student experience is this connection. This was useful in putting our ideas in perspective: "is [insert feature or action] facilitating a better connection?" was a question that was often asked.

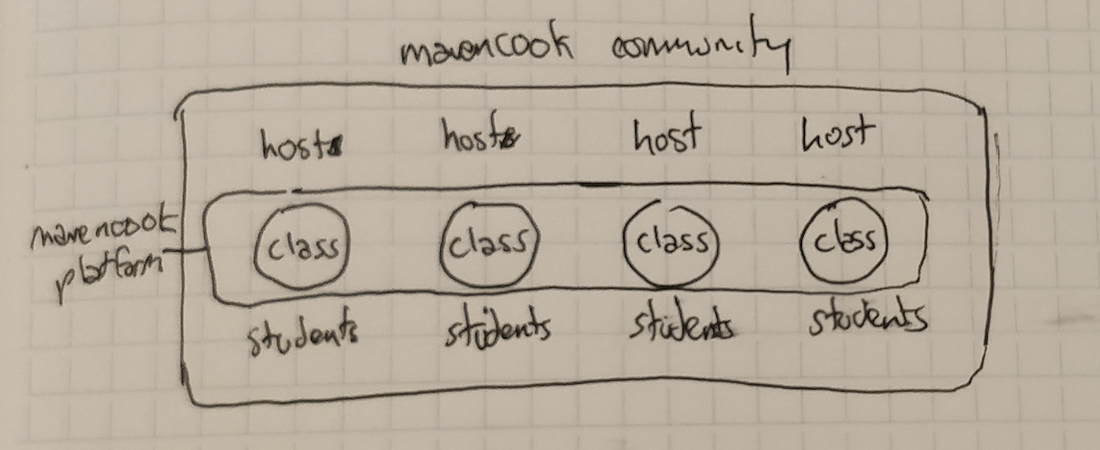

The final model is of the relationship between the platform and the community. The Mavencook platform consists of the set of all classes. We have hosts on one side of the platform, and students on the other side. The Mavencook community consists of the platform as well as both sides.

Reflections

I was working on a complete unifying model, but realized that it wasn't necessary - it was better in our case to have small, targeted abstractions working in different regimes that each completely fit specific use cases than a grand, elegant, unifying theory. (I feel the same way, to a point, about the reductionist view of physics...)

5

Flow and Prototyping

Abstract

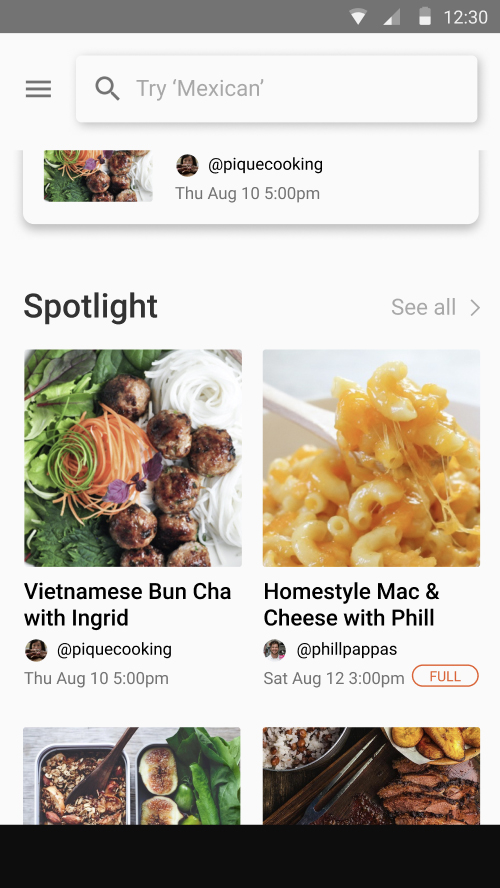

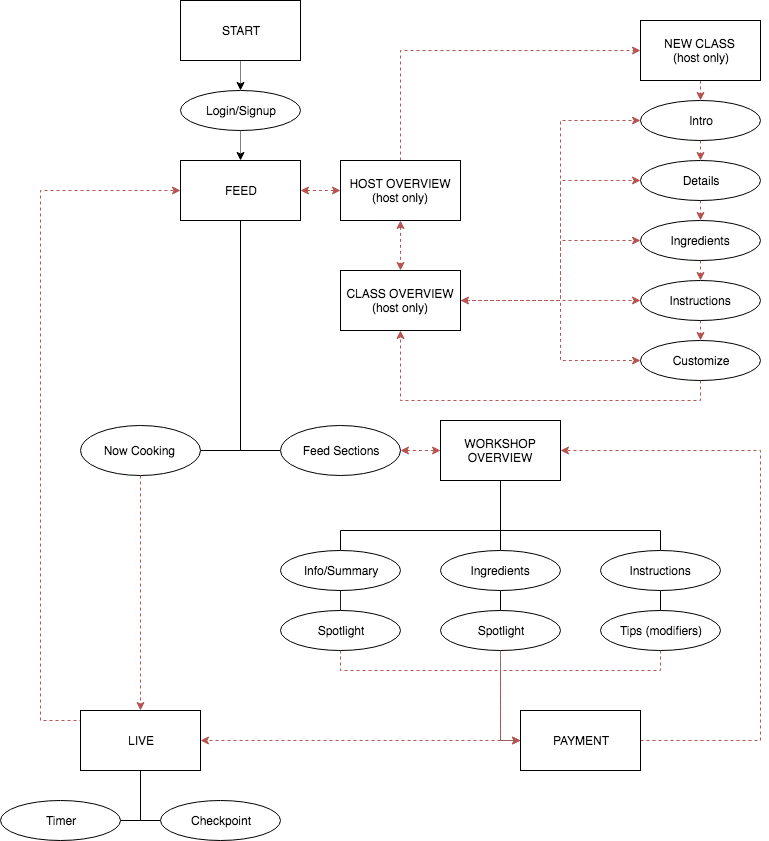

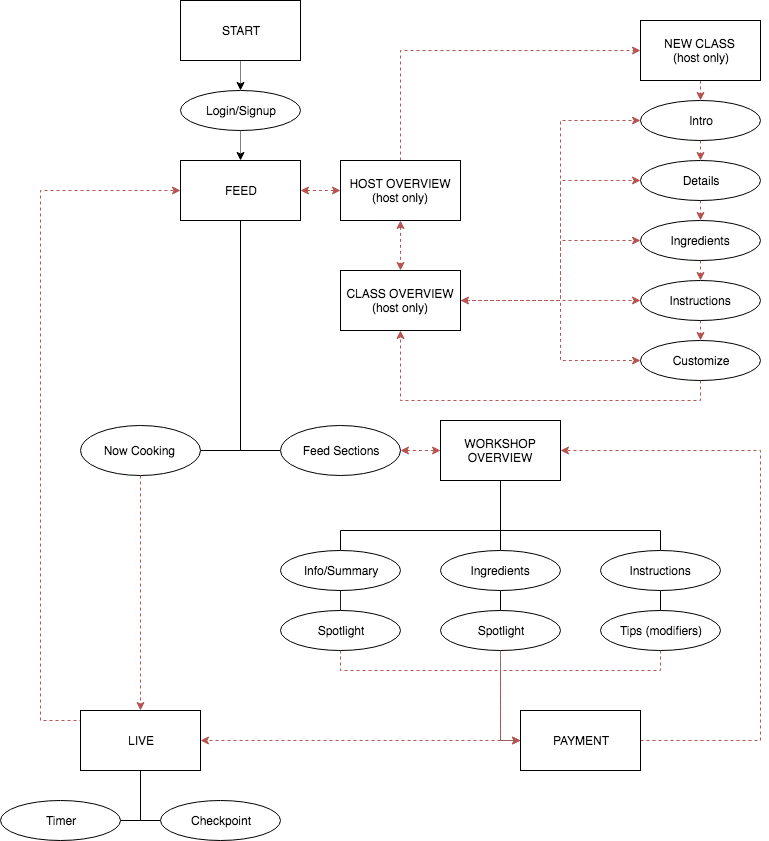

Creating the flow involved prioritizing features, sketching, collaborating with engineering, and many revisions. Here, I describe the details of this process and show the results.

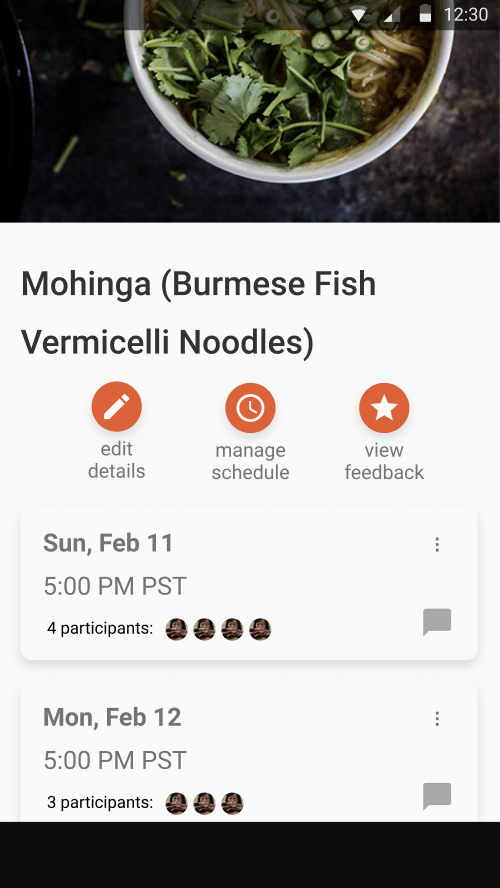

Creating the flow took place through a number of iterations. From our profiles and user stories, I highlighted a number of features and evaluated them in contexts including complexity, urgency, impact, and maturity. I went through a series of refinements, prioritizing development flows/features shared between both host and student users.

For each feature, I went through a process. I gathered insights from prior trials and ethnographies, identified bumps (pain points of a smaller scope), formed a case around it, and validated our assumptions behind the feature.

For example- in one test, two users were cooking at different speeds. The host had to continuously check in on the slower one without ignoring the faster one. To address this, we developed the idea of a 'checkpoint' feature - a quick indicator that would allow hosts and users to visually query for and represent the completion of a specific task. We conducted in-depth interviews about the applicable cases with hosts and introduced the idea to them. To validate, we had them teach the same recipes, thinking in the context with the checkpoint, and interviewed them afterwards.

I went through multiple rounds of sketches, wireframes, and prototypes involving feedback from engineering. When each iteration was complete, I consulted users and reevaluated priorities.

Reflections

My background isn't in UI, so I was learning as I iterated. This part was a lot of fun, and I realized how important it is to work closely with engineering in this process. It's easy to come up with excuses not to present incomplete work for fear of criticism, but I realized that it's better to get as many opinions from different backgrounds as possible in all parts of the process.

6

Design for Failure (wip)

A core piece of the experience we were creating focused on live videochat, and thus it relied heavily on a consistent internet connection. In the process of testing, I discovered that users had an acute emotional reaction to failure scenarios - students relied heavily on hosts for instruction, and even a short break in the connection evoked emotions such as fear, helplessness, and anxiety. When these situations resulted in mistakes in cooking, users manifested these emotions strongly, increasing the likelihood of negative associations with the experience.

"How might we design communications protocols to de-risk live cooking over an internet connection?"

By observing and mapping user emotions throughout testing, I identified two failure regimes in which users experienced significant negative emotion:

- Human Failure: When the video channel is stable but the user fails

- Connection Failure: When the users execute perfectly but the video channel fails

Human Failure

Research goals:

Understand the dynamics of user mistake scenarios in live video chat cooking instruction

Research method 1: Observational study

When students would make mistakes, I observed and recorded the scenario. I interviewed both hosts and students after each event.

Research method 2: Planned mistakes

I constructed scenarios and briefed the students beforehand. In the scenario, students would plan to make a mistake at a certain point, and we would observe how the host handled the scenario. I conducted interviews after each session.

Research results:

Case Study: Burning Caramel

In one session, a student was making caramel in parallel with another part of the dish. In the process, the student did not pay attention to the caramel, and ended up burning it. In the session, the host had instructed the student to pay attention to temperature, which was difficult to assess, and time, which varies depending on temperature. The host instructed the student to try again, and had the student describe any changes in detail, which resulted in success.

We discovered that students often do not know what to look for in cooking, and most recipes do not describe the correct indicators. Instead, recipes rely on more “objective” factors - chiefly, time. Timing is important, but timing is different from absolute time, which is the metric recipes traditionally use - as in, timing refers to correct execution of an action at the right point in time, whereas absolute time refers to the predetermination of when that right point in time is.

In cooking, we realized that absolute time is merely an approximation calculated from a number of different timing indicators for convenience of communication (or laziness). Examples of timing indicators include:

- Consistency (i.e. thick and smooth)

- Color (i.e. edges are browning)

- Behavior (i.e. bubbling)

- Features (i.e. skin begins to form)

In trials, the most successful hosts at handling mistakes were hosts that understood the high-risk steps in their own recipes. They would often preface their instructions with details about the risks, and thus mentally prepare their students for navigating those risks.

We concluded that we needed to revise our mental model of a recipe from a series of steps, to a series of actions, indicators, and consequences. We proceeded to outline ways to leverage the unique aspects of live videochat to communicate indicators efficiently and effectively.

Connection Failure

Research goals:

Understand the dynamics of internet connection failure in live video chat cooking instruction

Research method 1: Observational study

Our first working prototypes did not have a completely stable video connection. When connections would fail naturally, we would carefully observe and record the situation. We interviewed both hosts and students after each scenario.

Research method 2: Planned mistakes

We set up a number of classes, and briefed the students beforehand. Before each session, students would plan to make a mistake at a certain point, and we would observe how the host handled the scenario. We conducted interviews after each session.

Research results:

Case Study: Halfway around the world

The first couple iterations of the app were buggy - it wasn’t optimized and relied heavily on a stable high-bandwidth internet connection. Problems would usually resolve themselves within a minute or two, except for one time when it refused to reconnect for about five minutes. When this happened, we were in the middle of a session with a host in New Delhi. Because of the spotty connection, the session took a lot longer than expected. The host and the users were cooking in parallel, so every break meant that instructions were cut off in the middle, and incomplete information was relayed.

In the beginning, all cooking instruction was conducted in parallel - that is, hosts have instructions in real time and observed students performing the same steps at the same time. Not only was this difficult for hosts, but there was a glaring liability: if the connection was interrupted, students were often left hanging in the middle of a step with no idea what to do next, greatly increasing the probability of mistakes. Additionally, hosts had to gauge user skill level in real time, and keep track of the phone screen as well as their own work station.

In cooking schools, teachers will perform a recipe in full first as a demonstration, and then students will execute as instructors circulate and observe. The benefit of such an approach is that an instructor’s full attention can be dedicated to the students during execution. The drawback is that it takes a lot of time.

Reflections: This was a tough one, and something that I was working on through a large portion of the process. The world of failure is interesting - ideally, only a very small percentage of the userbase would experience it, but because of the severity of the situation it was incredibly important to dedicate time to getting it right. Ideally, I would have created a lot of different scenarios to test and observe reactions, but this was a huge project in and of itself - so I had to make a lot of decisions based on limited time and priorities. This is only one iteration on the journey, and it really drove home to me how important it is to explore all possible edge cases.

7

Results and Takeaways

We launched an alpha version to a small group of users and received positive feedback. All of our hosts were volunteers, who continued teaching after the alpha was officially over. A majority of students came back and booked more classes.

I learned a lot from taking a product from idea phase to launch. Because the idea I was approahed with was incredibly broad in both scope and target, I had to continuously redefine the problem as work progressed. In this search, I reached out to subjects including education, navigation, and communication for inspiration.

- A product is more than what you see - it consists of so many different components working together behind the scenes: Brand, Identity, Application, Community, Protocols, Standards. These elements all come together to form an ecosystem. There is so much more than meets the eye, and I learned a lot from building it from the ground up.

- Build bridges, not silos - working together with and getting feedback from engineering throughout the whole process was very important to building a great product. Sharing knowledge across diverse backgrounds and tackling challenges together often led to more novel, cohesive, better solutions. The process of building a product is nonlinear and things change quickly. It was only through working together that we could adapt to changing priorities easily and effectively.

- Fail fast, and validate everything - it's the best way to move forward. A bunch of invalidated assumptions do not equate to one large failure - in fact, it's usually the opposite. Continunously testing and validating helped me realign myself often and spot mistakes way before they became catastrophic.